Sears, Please Hold

A.D. Freudenheim, The Editor

The tap water in our building has been going downhill lately. It might be because the city has shut the water off a few times lately – and every time it comes back on, the pipes are flush with sediment. Or maybe the building’s own diligent plumbing efforts are the culprit, as 50+ year old piping is replaced – and again, there is more sediment in the water. Buying gallon after gallon of drinking water is not especially efficient, either in terms of price, storage, or use of plastic, so I have been looking into a filter for the kitchen sink. Consumer Reports gave good marks to two affordable, under-the-sink units made by Kenmore, an in-house brand of Sears. I looked, I did some additional investigating, and I decided to buy the Kenmore 2-Stage Drinking Water Filter, Model #38461.

I also wanted to order extra replacement filter cartridges; after all, why pay for shipping twice? Except: not so fast, buster. That information is virtually a trade secret!

***

Sears has been in the news a lot lately. Chairman Eddie Lampert was profiled in The Economist and the New York Times, and neither painted an overly optimistic view of the business, despite efforts to compare Lampert to investor Warren Buffet. Sears’ profits are down, the company has been criticized for some stove-related product safety issues, and there’s no polite way to put this, but: when was the last time you shopped at Sears?

In my youth, the store was a staple retailer. Appliances came from Sears, and rough-and-tumble clothing came from Sears. Craftsman-brand tools were what we had on hand for any household project, back in the day before “DIY” was a lifestyle rather than just how we did things around the house. Which is why, when Consumer Reports gave the Kenmore water filter a good rating, I thought nothing of trying to order it.

***

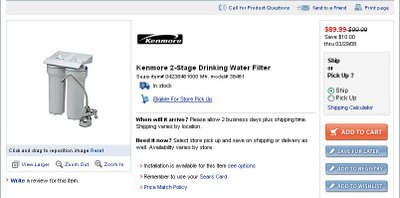

Placing an order for the water filter unit itself was no problem. The Sears.com web site indicated the product was available for shipping, and to complete the process would have been only a few clicks. But as I said, I wanted to order replacement filter cartridges, too. Except: the page for the filter does not provide the part number for the corresponding replacement cartridges. Really – go look for yourself. Even worse, if you search the site for “water filter,” you get more than 50 results, replacement filter cartridges included; but none of them indicates which model water filter they fit. No, not even in the so-called “Specs” section, which provided little information about any of these products.

In the interest of rapid resolution, I clicked on the little link that says “Call for Product Questions,” right above the product information (and shown on the picture here, too). A new window popped up, offering me an immediate call-back by putting in my phone number. I put my number in, and sure enough, within seconds the phone rang. “Cool!,” I thought, a system that works! A nice gentleman named Andrew answered, asked how he could help me, and I told him what I wanted; he said he would transfer me to the parts department, which would be able to answer my question. He said he’d put me on hold, which he did ... and then an automated female voice started asking me questions about which department I needed. At first I thought this was just part of the hold process, but then I realized I’d been transferred into this voice-activated system. I made a selection, the system responded that it would transfer me, and then after a few seconds I got a voice telling me my call could not be completed and I should hang up and try again. What?

I did just that. I went back to the web site call system, put in my number, and within seconds I had Andrew on the phone again. I told him I’d been cut off, repeated what I wanted, and he apologized. He said he’d put me on hold again while he got an actual person in the “Parts” department who could answer my question. A few seconds after that, I had a young woman with a bad, hard-to-hear connection asking me questions. Her first question? My phone number. Her next question? My last name. After that? My address.

How on earth is this relevant to a simple question: what is the matching replacement filter cartridge for the Kenmore 2-Stage Drinking Water Filter, Model #38461?

It isn’t relevant – and there wasn’t an answer. I do hope someone from those mysterious “Quality Assurance” teams goes back to listen to the recording of this call, because it’s a doozy. Eventually, the woman understood that I was trying to find a corresponding part, for which I didn’t have the model number. That it was because I didn’t have the model number, that it was because the model number for the replacement cartridge isn’t listed on the Sears.com filter unit page, that I was calling for help.

She couldn’t help me. Her suggestion? Call a store. Apparently, Sears stores – the actual stores – have a cross-referencing catalog that tells them which parts go with which products. Apparently, Sears.com staff do not have this nifty resource available to them. Just to make sure I understood this scenario properly, I asked the question just that way: the store has information that you don’t have? Yes, she said. The connection was too crappy and her voice too soft for me to tell whether there was a hint of embarrassment in this answer. If not, there should have been.

***

I called Sears, the store at the Galleria Mall in Poughkeepsie, New York, which I knew I’d be able to visit in short order if I wanted. I got an automated voice that offered me a list of “popular” departments. Which department does a water filter fall under? I had to call three times before I figured out that even though “plumbing” wasn’t one of the menu items automatically listed, the system would respond when I asked. (I had already tried saying “Help,” which got me an “I didn’t understand your request” response. Saying “Customer Service” got me transferred into some broader Sears system that wasn’t specific to the Poughkeepsie store.)

I asked for “plumbing,” and the system transferred me. The phone rang, and rang, and rang some more. Eventually, it was answered: by an answering machine that told me that no one was available to help me, but that if I left a message with my name and number, someone would call me back.

No, thanks, Sears. At this point, I’m not sure I would speak with Mr. Lampert if he called me personally. What else is there to say? In its article from 29 January, the Times quoted a memo Lampert wrote in which he said “I remain confident in our ability to ultimately succeed, even if there are steps backward along the way.” If any retail business analysts out there were looking for an example of what he meant by “steps backward,” I think I have an answer for you.

***

UPDATE: Sears responded to me. Read about that here.